Table of Contents

Who is Professor Enos Kiremire?

Prof. Enos Masheija Rwantale Kiremire is a Ugandan inorganic chemist, inventor, and academic whose life’s work has bridged continents and generations of scientific discovery. Born on February 18, 1945, in western Uganda, he rose from a curious student and talented athlete at King’s College Budo—where his sprinting skills earned him the nickname “Wantari”—to an internationally recognized scientist holding seven World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) patents. A graduate of Makerere University College, then part of the University of East Africa, he fled Uganda in 1971 during Idi Amin’s regime and pursued his PhD at the University of New Brunswick in Canada, where he was the only Black student in his department.

Over the decades, Kiremire built an illustrious career teaching and researching at universities across Africa, including Zambia and Namibia, where he served as Dean of the Faculty of Science. His groundbreaking “Chemical Cluster Theory” has simplified how chemists understand and predict molecular structures, while his patented compounds hold promise for antimalarial drug development. Despite enduring political exile, culture shock, and personal tragedy—including the loss of his wife in 2018—Prof. Kiremire remains a devoted mentor and advocate for science education in Uganda. Now in his 80s, he continues to inspire young scientists to see chemistry not merely as formulas and reactions, but as a force for human progress.

What did he tell Kampala Edge Times?

Prof. Enos Masheija Rwantale Kiremire opened up about a life dedicated to unraveling the mysteries of inorganic chemistry. At 80 years old, the retired professor, who returned to Uganda in 2018 after decades abroad, remains a beacon of resilience amid political turmoil, cultural shocks, and personal loss. His story, from a nickname-earning athlete in secondary school to holding seven international patents, underscores a passion for science that began with simple arithmetic and evolved into tools that could revolutionize drug development against diseases like malaria.

Early Life and Athletic Nickname

Born on February 18, 1945, in western Uganda, Kiremire’s early years were marked by curiosity and athletic prowess. “I could run 100 yards, 800 meters, and 220. I can sprint. And I was also a winger, left winger, left-footed,” he recalled with a chuckle, explaining how his speed earned him the nickname “Wantari” from fellow students at King’s College Budo, where he completed his secondary education in 1964. His full name—Masheija Rwantare—stemmed from his father’s, adopted formally later in life. “Students gave me the name Wantari, which was a nickname, and I kept it,” he said, reflecting on how youthful labels shaped his identity.

University Education in a Changing East Africa

From Budo, Kiremire advanced to A-levels at Makerere College School, then enrolled at Makerere University College, part of the University of East Africa—a federation that included institutions in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam. He graduated in 1970 with a Bachelor of Science honors degree in chemistry, physics, and mathematics, making him one of the last alumni of the short-lived university before it splintered in 1971. “The University of East Africa comprised Makerere University College, University of Nairobi, University of Dar es Salaam,” he explained. “After ’70, when we graduated, the university split up.”

First Job and the Shadow of Political Turmoil

His early career began promisingly. After a six-month stint at the Namulonge Cotton Research Station near Kawanda, where he contributed to agricultural research, Kiremire returned to Makerere as a staff development fellow. The role was meant to pave the way for a lectureship upon earning advanced degrees. But Uganda’s political landscape shifted dramatically in 1971 under Idi Amin’s regime. “That nightmare I said, ‘Look, I cannot continue here. I must go abroad,'” Kiremire recounted. Amid disappearances and spelling checks at checkpoints that targeted intellectuals, he secured a Commonwealth Scholarship to Canada.

Culture Shock and Academic Triumph in Canada

Arriving at the University of New Brunswick as the only Black student in his chemistry department, Kiremire faced a profound culture shock. “You’re scared of getting out because you’re the only Black face,” he admitted. “You walk around, you walk into the main road, you find you’re the only Black face. Your department, you’re the only Black face.” Children would peer at him in the library, and he felt constantly monitored, though outright racism was absent. “They look at you as a strange person,” he said. Yet, his talent shone through. After delivering a seminar that impressed faculty—”They were surprised to understand things”—his master’s registration swiftly upgraded to a PhD, which he completed successfully.

Post-PhD in 1977, Kiremire sought opportunities outside Uganda, where Amin’s terror reigned. Job offers came from the Universities of Zambia, Lesotho, and Botswana. He chose Zambia, drawn by the community of Ugandan exiles, including political figures like Eriya Kategaya, Amama Mbabazi, Dr. Doris Akumu, and Dr. Lule. “I start to go back to Zambia because they are Ugandan,” he said. There, he rose from junior lecturer to associate professor over 25 years.

A Serendipitous Christmas Romance

Amid his professional ascent, love blossomed. On Christmas Day 1964, while home from school, Kiremire spotted his future wife at a church service in Kavari. “I saw that good looking,” he said simply. Ignoring the sermon, he followed her group seven kilometers home, catching up halfway to declare his interest. “It clicked like this,” he described, with no drama. She was studying at Kawala, later transferring to Gayaza High School. They dated for seven years via aerograms, as phones were scarce, marrying in March 1971 when he was 26. “If you reach 30 without marriage, very important time,” he advised, noting many relatives delayed longer.

Their union produced three children, each with dual degrees: a daughter, now 21 years into her medical career at Uganda’s Ministry of Health with a BSc in Human Biology, MBChB, and pursuing a master’s in psychiatry; a son who is an engineer; and another in business administration. Tragedy struck in 2018 when his wife, his “girlfriend, sister, mother,” died in a car accident with her brother while he was in Namibia. “How am I going to stand a life of wrongness in Namibia?” he pondered, deciding to stay in Uganda. “I’ve lived with this woman, dated this woman, lived with her all these years. Produced three children. They’re all grown ups.”

Academic Journeys Across Africa and Beyond

Kiremire’s academic odyssey continued. After Zambia’s economic woes—where “things were very expensive, you couldn’t save much money”—he moved to the University of Namibia in 1996, serving 17 years as Dean of the Faculty of Science. Interludes included a NAFL fellowship at the University of Sussex, UK; a visiting professorship at the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa; and a visiting scholarship at the University of Michigan, USA, in 1991. “People here say Michigan, Michigan,” he laughed, mimicking local pronunciations.

Back in Uganda, reintegration was swift. Relatives hosted him for eight months at Hotel Continental, owned by his nephew and Esther Rwantare, providing free meals. “They didn’t charge me a single shilling because these are my people,” he said. An interview at Kyambogo University was derailed when family lobbied President Yoweri Museveni—a contemporary from 1960s university days—to intervene. “He was my contemporary… doing senior four, I was doing senior four,” Kiremire noted. Museveni, two or three years older, had visited his Makerere dorm.

From Classroom Curiosity to Patent-Holding Innovator

Yet, Kiremire’s true legacy lies in his innovations. His passion for science ignited in junior secondary with arithmetic—”Two plus two equals four. You loved that”—evolving through geometry, algebra, and A-level chemistry experiments where “mixing this solution, color changes” captivated him. At university, chemistry dominated his studies.

In Zambia and Namibia, excitement from lab results spurred practical applications. “It’s science just for excitement? What about applications to help society?” he questioned. Focusing on drug discovery, he synthesized compounds tested for antimalarial activity at the University of California. Results showed high efficacy against Plasmodium parasites. “Why don’t we patent them?” a colleague urged. Local patents followed, but for global impact, they approached the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) in Switzerland.

Kiremire secured seven WIPO patents in 2011, lasting 20 years each until 2031, recognized in the US, India, Kenya, and South Africa with over 30 citations. “If we discover knowledge of some industrial application, you put it in the language by with legal people, then comes a patent,” he explained. “Somebody to buy that to get the knowledge, you must pay.”

These patents cover methods for synthesizing anti-malarial compounds, enabling pharmaceutical firms to develop new drugs. “The drugs companies run for a return to drug against malaria, they can take that knowledge, convert it into a drug,” he said. Monitoring usage falls to university commercialization departments, though he notes it’s a “gray area” where benefits may go unpaid.

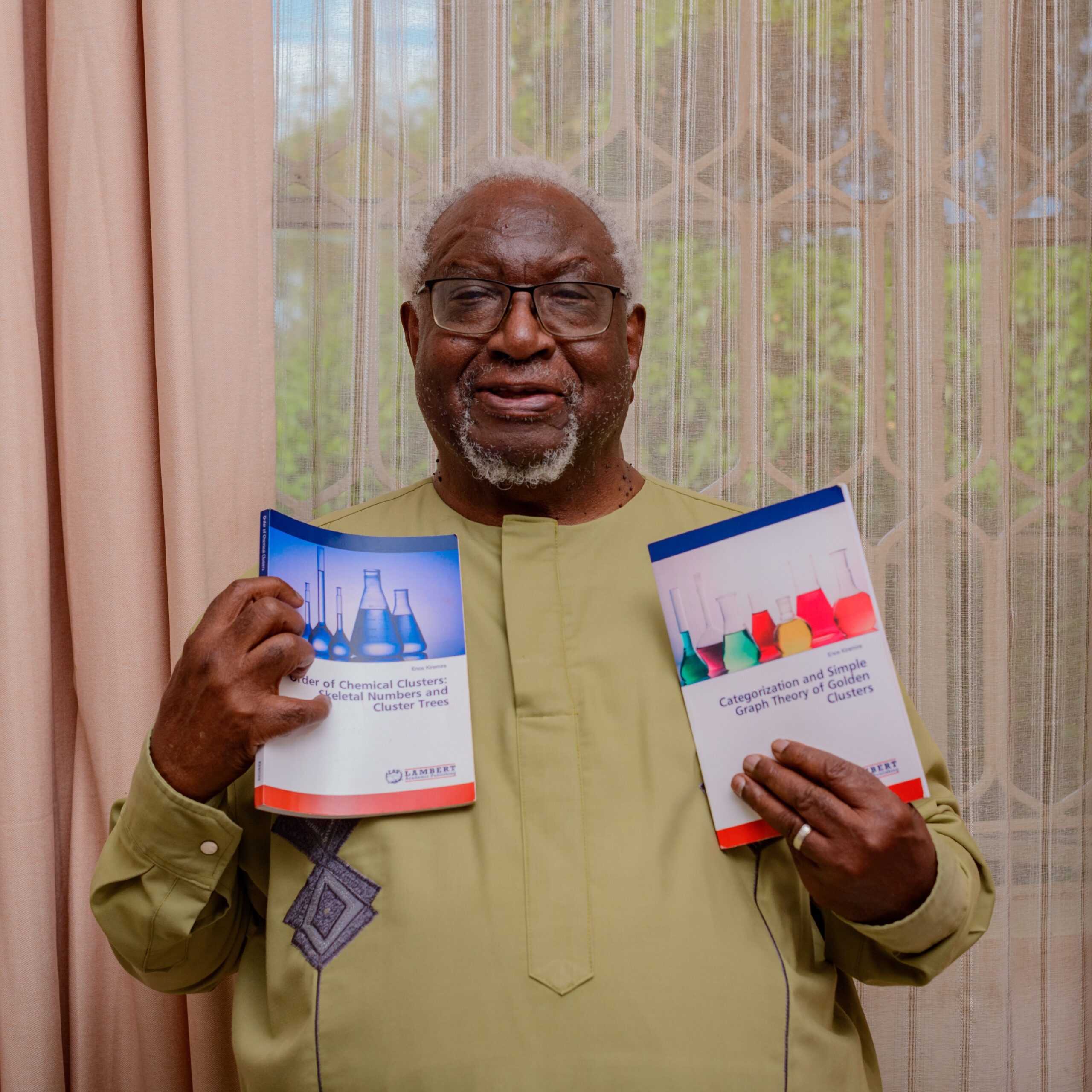

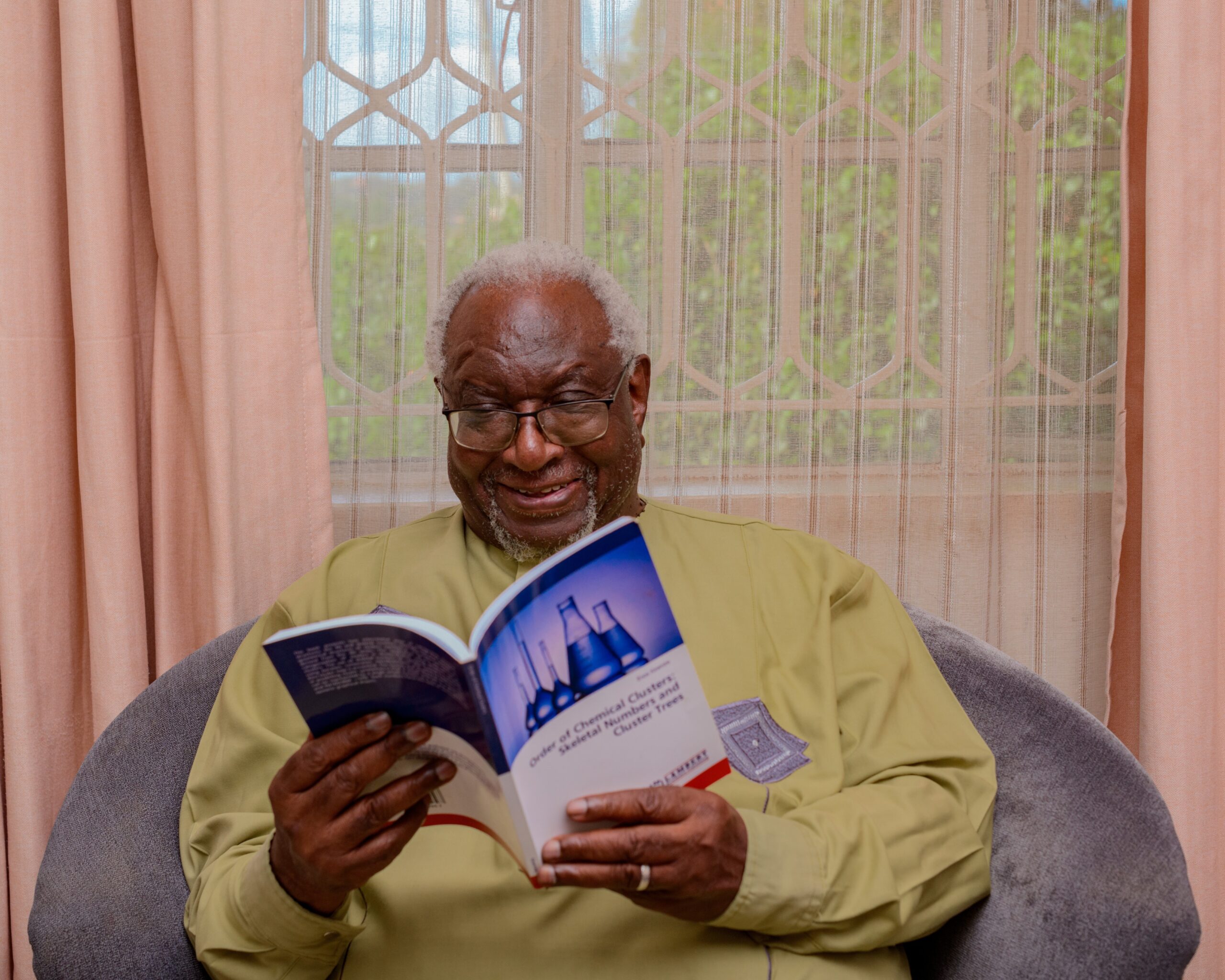

The Chemical Cluster Theory: Simplifying the Complex

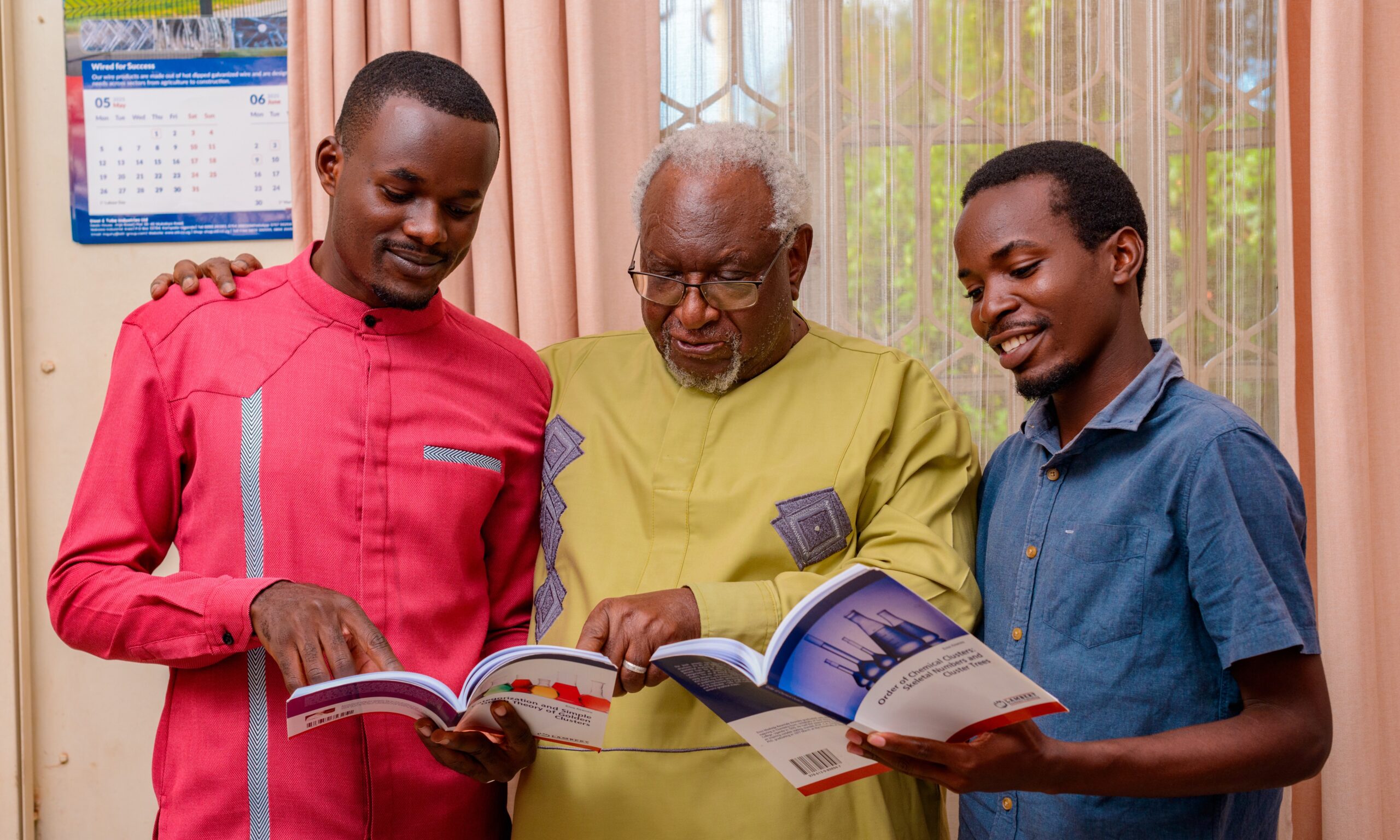

Kiremire’s crowning achievement is the Chemical Cluster Theory, developed over 20 years to simplify molecular structures. Posing, “Can this chemical compound be put in a group in order, like group one, group two?” he devised a system extending the periodic table to compounds. “Starting with the numbers, ended up in science,” he traced, from atomic numbers (discovered circa 1915 by Thomson, Rutherford, and others) to his 2015 “skeletal numbers”—values at elements’ bases predicting bonds and shapes.

Skeletal numbers, like 2.5 for nitrogen or 0.5 for hydrogen, allow grouping any formula—e.g., water (H₂O) into clusters revealing two bonds and eight electrons. “It helps you put life into formula,” he said, bypassing costly measurements like infrared spectroscopy or NMR for faster drug design. Applications span boron compounds, metal carbonyls, zeta ions, and gold clusters, explaining reactions in fertilizers, alcohols, and antimalarials. “No single group of compounds which have been giving trouble to many scientists that cannot be explained by Cluster Theory,” he asserted.

Published via Lambert Academic Publishing and platforms like Amazon and eBay, his books advocate science education. “There’s no single Ugandan with the WIPO patents,” he noted humbly, shunning pride: “Say you are too proud… I don’t want somebody to get that.”

Family, Faith, and a Call for Investment in Science

Family remains his anchor. His daughter-in-law, from Kasese in western Uganda, described him as “a very family man” with “such a big heart.” Hosting relatives weekly, he values Christianity, people, and decisions aligning with God. “Whatever I do, the decisions that I make, I have to make sure that it doesn’t affect the person next to me, my family, and it has to be in line with God.”

As Uganda grapples with funding shortages for basic sciences—”Soon, it is going to be worse,” he warned in 2019—Kiremire urges investment in innovators like himself. His return, though born of grief, has reignited a mission: mentoring the next generation. “I’ve got seven patents… Well, they recognized with 28 citations,” he said modestly. In a world needing solutions for malaria and beyond, Prof. Kiremire’s story proves that from a sprint on Budo’s fields to patents in Geneva, one person’s numbers can change everything.